Design Life-Cycle

assess.design.(don't)consume

Katelyn Buccinio

Professor Cogdell

DES 040 Winter 2014

March 13, 2014

Apple iPad Materials

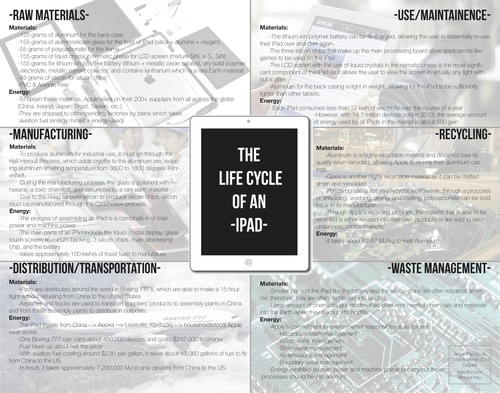

In today’s day and age, technological devices are so numerous that they outnumber people. Due to the large use of devices such as computers, iPads and cellphones, the materials and energy that it takes to make these devices is tremendous. In my research, I looked at the life-cycle of one specific technological device, the iPad, and the materials that go into making this product. Designed and created by Apple Incorporated, the iPad is made up of materials from all over the world that are then manufactured into this “one-of-a-kind” product. Due to the consumer demand and changes to the design and software, the Apple iPad is a “cradle-to-grave” product; however, Apple is striving to create a “cradle-to-cradle” product with more efficient and recyclable materials.

The Apple iPad consists of many components that ultimately make up this inventive product. However, I will look at the lifecycle of the iPad as a whole before examining the individual lifecycle of each material that goes into making this product. Weighing only 1.44 pounds and measuring between 0.29 and 0.34 inches thick, the iPad has a slim and sleek design.[1] Due to its compact size and weight, you may think that the iPad does not consist of many materials; however, the iPad uses many different kinds of metals, including aluminum, silicon and steel along with trace amounts of rare earth materials and chemicals. All of these materials come from companies or are acquisitioned from places around the world.

Apple is a master of “global manufacturing” when it comes to its products.[2] The manufacturing of the iPad is known as one of the “fastest and most sophisticated manufacturing systems on Earth.”[3] Assembled in China by a company known as Foxconn, the Apple iPad is an accumulation of highly designed and manufactured products such as the LCD screen and the aluminosilicate glass which create a durable, high-class product. However, the manufacturing process of the iPad takes a great amount of energy and is responsible for 58% of the greenhouse gas emissions in the whole iPad lifecycle.[4] Specifically, one iPad uses 100 kilowatts of fossil fuels which result in 66 pounds of carbon dioxide.[5] Therefore, assemblage of the iPad is done in China by Foxconn due to the lower greenhouse gas emission standards and lower overall working standards by the Chinese government. Although China allows the manufacturing of Apple products with their high greenhouse gas emissions, Apple is trying to reduce the amount they emit by using more recyclable materials such as aluminum and glass and by reducing the amount of chemicals and toxic materials in their products by making such components as the aluminosilicate glass PVC-free and arsenic free.[6]

The global manufacturing of Apple iPad components and their dispersal for use worldwide begs the question of how Apple transports their products for consumer use. According to one report, Apple uses air and land transport to move products from suppliers to assembly plants in China and from these assembly plants to distribution outposts around the world. Specifically, Apple employs Boeing 777’s to carry products around the world as these airplanes are efficient, making a 15 hour flight from China to the United States without refueling.[7] Like with the manufacturing stage of the iPads lifecycle, Apple is trying to create more efficient and environmentally friendly ways of putting their products out into the global technological market.

Once in the consumers’ hands, the Apple iPad has many uses. It can be used as a computer with Internet and Wi-Fi or as a tablet to read books among many other things. All of these applications are made possible by the efficient silicon chips that make up the main processing board of the iPad. Although the use of the iPad makes up 30% of the total greenhouse gas emissions in the iPad lifecycle, the lithium-ion polymer battery set inside the iPad can be recharged.[8] Thus, a consumer can, in a sense, re-use the iPads’ battery as it does not need to be replaced after the charge is gone but can be continuously re-used over a long period of time. This is another component of the iPad that is more efficient than previous products and that promotes a “cradle-to-cradle” lifecycle.

Finally, Apple has produced a recycling project that takes the recyclable material of the iPad and re-uses them in their own products or is sold in a secondary electronics market.[9] These recycling projects send old iPads to places like India where workers disassemble the products for bits of material that can be recycled or sold back to companies that can refurbish them.[10] Aluminum, glass, and plastic are some materials from the iPad that are easily recycled and re-used. However, due to trace amounts of gold and rare earth materials which cannot be recycled, some components of the Apple iPad still ends up in landfills where they may sit for decades, emitting harmful chemicals and materials into the Earth.

Now let us look at the major components of the iPad and their lifecycles individually. According to iFixit, the iPad consists of a back case, screen, frame, LCD screen, chips, and battery among other things.[11] Beginning with the iPad’s outer shell, the back case is made out of aluminum. Aluminum, the most abundant metal in the Earth’s crust has a low density and resists destruction, making it the perfect material for the slim and delicate Apple iPad.[12] Therefore, in one iPad, 125 grams are made from aluminum, resulting in about 17% of the total weight of the iPad consisting of aluminum.[13] Although aluminum is abundant in the Earth’s crust and comprises a large amount of the iPad structure, aluminum is hard to extract for industrial use. Consequently, bauxite, an aluminum ore, must be acquisitioned from the Earth’s crust.[14] Then, through the Hall-Heroult process, aluminum is prepared for industrial use. Due to the difficulty in extracting aluminum from its ore the Hall-Heroult process adds cryolite, a mixture of alumina and sodium fluoride to bauxite.[15] Cryolite reduces aluminum smelting temperature from 3600 to 1800 degrees Fahrenheit.[16] This extraction process takes a lot of power, from 52 to 56 MJ/kg.[17] Once extracted and prepared for industrial use, Apple relies on Alcoa Inc. to make the aluminum back casing. Alcoa Inc. is the third largest producer of aluminum in the world with factories worldwide from Jamaica to Russia.[18] Alcoa uses coal-fired power plants, causing them to be ranked 15th among corporations emitting airborne pollutants like sulfur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide.[19] Although it takes a lot of energy to produce and it emits a lot of airborne pollutants, aluminum is a highly recyclable material. Aluminum is a material whose quality does not degrade when recycled. Therefore, recycling aluminum is not only beneficial to the environment, but it also saves new Apple products from consuming more aluminum. Therefore, Apple tends to recycle this aluminum as backing for other iPads or for smaller components of their products, creating a more efficient production cycle along the way. Moving to the front of the iPad, the outer screen is made from glass. The glass is 155 grams or about 21% of the overall iPad’s weight.[20] Although the entirety of the iPad’s front is made out of glass, it is debated whether this glass is aluminosilicate glass or regular glass. Many believe that the iPad consists of aluminosilicate glass made by the company Corning.[21] This type of glass is a mixture of silicon dioxide, aluminum and oxygen which makes the glass more resilient than regular glass made from silica, limestone and potash.[22] According to Apple, the iPad’s glass enclosure is PVC-free and arsenic free.[23] However, reports of explosions in the Chinese assemblage factories of Apple products have found that toxic chemicals such as n-hexane, which can cause nerve damage in humans, have been used to clean the glass screens of iPads and other Apple products.[24] Cerium oxide, a rare earth material, is also used by Apple to polish the glass screens.[25] Although these materials and chemicals may be used to polish the front of the iPad, the glass can still be recycled. As noted earlier, Apple sends its products to be disassembled in other countries such as India where the glass is removed from the iPad and sold back to its manufacturers, who can melt the glass into liquid and then reheat it into another mold. Even though aluminasilicate glass may be rendered with more chemicals to make it more resilient, it still has the ability to be re-used in other products or in other forms, making it follow the “cradle-to-cradle” standards Apple is striving to set.

Underneath the iPad’s glass is a frame made of plastic. Plastics make up only 55 grams of the Apple iPad.[26] Apple uses polycarbonate plastic, a tough and stable plastic, which like other plastics comes from oil and are built by chemists.[27] Although it can be easily molded like glass, plastic is not as recyclable, due to the fact that plastics quality degrades when repurposed or recycled. Therefore, the plastic that Apple uses in iPads often accumulates in landfills for decades or is removed by those who disassemble Apple products and goes through a process of shredding, washing, drying and melting into smaller components that then can be sold back to plastic manufacturers such as Coxon.[28]

The LCD screen, the most expensive part of the iPad, is made from liquid crystals in what is known as the nematic phase.[29] The LCD display on an iPad takes up 155 grams or about 21% of the overall weight of an iPad.[30] Manufactured in clean buildings by robots, LCD screens are a mixture of the chemical elements SiN, a-Si, and SiN, with a layer of polyamide alignment film for cleaning.[31] Sitting between two polarizers, the LCD display relies on liquid crystalline substances in the presence or absence of an electric field.[32] The LCD screen is the most significant component of the Apple iPad as it allows the customer to view the screen in virtually any light and in any space without the presence of a glare. Even though the LCD screen is a thin layer in the iPad, it has great importance to the overall iPad as a product. However, it is unknown if Apple’s disassembling team takes the time to keep the LCD screen or if it goes to waste in landfills around the world.

Another significant component of the Apple iPad is the lithium-ion polymer battery. Sitting inside the iPad, the battery takes up 155 grams or 21% of the overall weight of an iPad.[33] The lithium supply for these batteries is in South America, most notably Argentina, Bolivia and Chile.[34] The lithium is combined with a metallic oxide catalyst, a dry solid polymer electrolyde and a metallic current collector.[35] To produce the battery, its producers require somewhere around 79 gallons of water per battery.[36] The battery in Apple products is free of lead, cadmium, and mercury; however, it is believed to contain rare earth materials such as lanthanum.[37] Once produced, the battery can be recharged over and over again, allowing one battery to be re-used for every iPad. Lithium-ion polymer batteries, like all batteries, can be recycled as well, causing them to be an efficient component of the iPad.

Finally, at the heart of the iPad and essential to its operations are three silicon chips made from silicon and trace amounts of chemicals. Silicon is found in sand, dust, and forms of silicon dioxide.[38] China, Russia, Norway, Brazil and the United States are the leading suppliers of elemental silicon.[39] However, due to the need for pure silicon to produce digital chips, companies like Samsung must mine and manufacture silicon through a process known as the Czochralski process.[40] This method is relatively cheap compared to other methods and can make a lot of pure silicon at once.[41] Silicon chip manufacturing begins in very clean buildings where robots do most of the work. Silicon wafers are produced through a heating and cooling system and then printed on through photolithography.[42] This process uses numerous chemical coatings to produce a digital chip like the ones in the iPad. However, the need for an extremely clean environment and different chemicals to produce a strong and stable chip causes silicon chips to be hard to re-use. It is only recently that silicon chips are being recycled into solar panels by IBM; however, Apple does not seem to be making the same strides in the recycling of silicon chips and consequently are bringing more waste to landfills.[43]

The production of the Apple iPad is a global effort with many materials acquired and assembled around the world. Consequently, the life cycle of an iPad is complex as some of these materials, such as aluminum and glass, are highly recyclable while others, such as the trace amounts of rare earth materials, cannot be extracted to be recycled. Therefore, while aluminum and glass can be recycled and cause reduction in the need to extract more raw materials from the Earth, other materials spend decades in landfills, seeping toxic chemicals into the Earth. While Apple is looking toward ways to make their iPads more environmentally friendly, it is still considered a “cradle-to-grave” product, but one that is unmistakably highly sought after.

[1] Apple Inc., "Apple-iPad-Compare iPad models." Last modified 2014. Accessed February 24, 2014. https://www.apple.com/ipad/compare/.

[2] Duhigg, Charles, and David Barboza. "In China, Human Costs Are Built Into an iPad." The New York Times, January 25, 2012. http://www.teamsters952.org/In_China_Human_Costs_are_built_into_an_ipad.PDF (accessed February 15, 2014).

[3] Duhigg, Charles, and David Barboza. "In China, Human Costs Are Built Into an iPad." The New York Times, January 25, 2012. http://www.teamsters952.org/In_China_Human_Costs_are_built_into_an_ipad.PDF (accessed February 15, 2014).

[4] Apple Inc., "iPad Environmental Report." Last modified April 03, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014. http://images.apple.com/environment/reports/docs/iPad_Environmental_Report.pdf.

[5] Goleman, Daniel, and Gregory Norris. "How Green Is My iPad?." The New York Times, April 04, 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2010/04/04/opinion/04opchart.html?_r=0 (accessed February 8, 2014).

[6] Apple Inc., "iPad Environmental Report." Last modified April 03, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014. http://images.apple.com/environment/reports/docs/iPad_Environmental_Report.pdf.

[7] Satariano, Adam. "The iPhones Secret Flights from China to your Local Apple Store." Bloomberg, September 11, 2013. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-09-11/the-iphone-s-secret-flights-from-china-to-your-local-apple-store.html (accessed February 13, 2014).

[8] Apple Inc., "iPad Environmental Report." Last modified April 03, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014. http://images.apple.com/environment/reports/docs/iPad_Environmental_Report.pdf.

[9] Apple Inc., "Apple and the Environment." Last modified 2014. Accessed February 25, 2014. http://www.apple.com/environment/.

[10] Apple Inc., "Apple and the Environment." Last modified 2014. Accessed February 25, 2014. http://www.apple.com/environment/.

[11] iFixit, "iPad Wi-Fi Teardown." Last modified 2014. Accessed February 25, 2014. http://www.ifixit.com/Teardown/iPad Wi-Fi Teardown/2183.

[12] Shakhashiri, . "Chemical of the Week: Aluminum." lecture., University of Wisconsin, 2008. http://scifun.chem.wisc.edu/chemweek/PDF/Aluminum.pdf.

[13] Apple Inc., "iPad Environmental Report." Last modified April 03, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014. http://images.apple.com/environment/reports/docs/iPad_Environmental_Report.pdf.

[14] Shakhashiri, . "Chemical of the Week: Aluminum." lecture., University of Wisconsin, 2008. http://scifun.chem.wisc.edu/chemweek/PDF/Aluminum.pdf.

[15] Shakhashiri, . "Chemical of the Week: Aluminum." lecture., University of Wisconsin, 2008. http://scifun.chem.wisc.edu/chemweek/PDF/Aluminum.pdf.

[16] Green, John. Aluminum Recycling and Processing for Energy Conservation and Sustainability. Materials Park, OH: ASM International, 2007. http://books.google.com/books?id=t-Jg-i0XlpcC&pg=PA198&hl=en

[17]Green, John. Aluminum Recycling and Processing for Energy Conservation and Sustainability. Materials Park, OH: ASM International, 2007. http://books.google.com/books?id=t-Jg-i0XlpcC&pg=PA198&hl=en

[18] Alcoa Inc., "Alcoa:About:Locations." Last modified 2014. Accessed February 26, 2014. https://www.alcoa.com/global/en/about_alcoa/map/globalmap.asp.

[19] "The Toxic 100 Air Pollutants." lecture., University of Massachusetts Amherst, 2013. http://www.peri.umass.edu/toxicair_current/.

[20] Apple Inc., "iPad Environmental Report." Last modified April 03, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014. http://images.apple.com/environment/reports/docs/iPad_Environmental_Report.pdf.

[21] Braga, Matthew. Jamie & Adam Tested, "What's So Special about iPhone 4's Aluminosilicate Glass." Last modified June 14, 2010. Accessed February 26, 2014. http://www.tested.com/tech/smartphones/429-whats-so-special-about-iphone-4s-aluminosilicate-glass/.

[22] Braga, Matthew. Jamie & Adam Tested, "What's So Special about iPhone 4's Aluminosilicate Glass." Last modified June 14, 2010. Accessed February 26, 2014. http://www.tested.com/tech/smartphones/429-whats-so-special-about-iphone-4s-aluminosilicate-glass/.

[23] Apple Inc., "iPad Environmental Report." Last modified April 03, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014. http://images.apple.com/environment/reports/docs/iPad_Environmental_Report.pdf.

[24] Duhigg, Charles, and David Barboza. "In China, Human Costs Are Built Into an iPad." The New York Times, January 25, 2012. http://www.teamsters952.org/In_China_Human_Costs_are_built_into_an_ipad.PDF (accessed February 15, 2014).

[25] Freudenrich, Craig. How Stuff Works, "How Plastics Work." Last modified 2014. Accessed February 13, 2014. http://science.howstuffworks.com/plastic.htm.

[26] Apple Inc., "iPad Environmental Report." Last modified April 03, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014. http://images.apple.com/environment/reports/docs/iPad_Environmental_Report.pdf.

[27] Freudenrich, Craig. How Stuff Works, "How Plastics Work." Last modified 2014. Accessed February 13, 2014. http://science.howstuffworks.com/plastic.htm.

[28] Freudenrich, Craig. How Stuff Works, "How Plastics Work." Last modified 2014. Accessed February 13, 2014. http://science.howstuffworks.com/plastic.htm.

[29] Lundstrom, Daniel, and Jan Yilbar. "Liquid Crystal Material." Accessed February 12, 2014. http://www.kth.se/fakulteter/_TFY/kmf/lcd/lcd~1.htm.

[30] Apple Inc., "iPad Environmental Report." Last modified April 03, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014. http://images.apple.com/environment/reports/docs/iPad_Environmental_Report.pdf.

[31] Lundstrom, Daniel, and Jan Yilbar. "Liquid Crystal Material." Accessed February 12, 2014. http://www.kth.se/fakulteter/_TFY/kmf/lcd/lcd~1.htm.

[32] Lundstrom, Daniel, and Jan Yilbar. "Liquid Crystal Material." Accessed February 12, 2014. http://www.kth.se/fakulteter/_TFY/kmf/lcd/lcd~1.htm.

[33] Apple Inc., "iPad Environmental Report." Last modified April 03, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014. http://images.apple.com/environment/reports/docs/iPad_Environmental_Report.pdf.

[34] Kumar, Aswin. Waste Management World, "The Lithium Battery Recycling Challenge." Last modified 2014. Accessed March 3, 2014. http://www.waste-management-world.com/articles/print/volume-12/issue-4/features/the-lithium-battery-recycling-challenge.html.

[35] "How it’s made Lithium Ion batteries" Recorded March 03 2008. Web, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HJrNCjVS0gk.

[36] Goleman, Daniel, and Gregory Norris. "How Green Is My iPad?." The New York Times, April 04, 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2010/04/04/opinion/04opchart.html?_r=0 (accessed February 8, 2014).

[37] Apple Inc., "iPad Environmental Report." Last modified April 03, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014. http://images.apple.com/environment/reports/docs/iPad_Environmental_Report.pdf.

[38] livescience, "Facts About Silicon." Last modified April 19, 2013. Accessed February 25, 2014. http://www.livescience.com/28893-silicon.html.

[39] livescience, "Facts About Silicon." Last modified April 19, 2013. Accessed February 25, 2014. http://www.livescience.com/28893-silicon.html.

[40] h2g2, "Czochralski Crystal Growth Method." Last modified January 30, 2003. Accessed February 28, 2014. http://h2g2.com/edited_entry/A912151.

[41] h2g2, "Czochralski Crystal Growth Method." Last modified January 30, 2003. Accessed February 28, 2014. http://h2g2.com/edited_entry/A912151.

[42] "How do they make Silicon Wafers and Computer Chips" March 05 2008. Web, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aWVywhzuHnQ.

[43] "IBM to recycle chips for solar panels." The New York Times, October 30, 2007. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/30/technology/30iht-ibm.4.8118325.html?_r=0 (accessed March 7, 2014)

Bibliography

Alcoa Inc., "Alcoa:About:Locations." Last modified 2014. Accessed February 26, 2014. https://www.alcoa.com/global/en/about_alcoa/map/globalmap.asp.

Apple Inc., "Apple and the Environment." Last modified 2014. Accessed February 25, 2014. http://www.apple.com/environment/.

Apple Inc., "Apple-iPad-Compare iPad models." Last modified 2014. Accessed February 24, 2014. https://www.apple.com/ipad/compare/.

Apple Inc., "iPad Environmental Report." Last modified April 03, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014. http://images.apple.com/environment/reports/docs/iPad_Environmental_Report.pdf.

Braga, Matthew. Jamie & Adam Tested, "What's So Special about iPhone 4's Aluminosilicate Glass." Last modified June 14, 2010. Accessed February 26, 2014. http://www.tested.com/tech/smartphones/429-whats-so-special-about-iphone-4s-aluminosilicate-glass/.

Duhigg, Charles, and David Barboza. "In China, Human Costs Are Built Into an iPad." The New York Times, January 25, 2012. http://www.teamsters952.org/In_China_Human_Costs_are_built_into_an_ipad.PDF (accessed February 15, 2014).

Freudenrich, Craig. How Stuff Works, "How Plastics Work." Last modified 2014. Accessed February 13, 2014. http://science.howstuffworks.com/plastic.htm.

Green, John. Aluminum Recycling and Processing for Energy Conservation and Sustainability. Materials Park, OH: ASM International, 2007. http://books.google.com/books?id=t-Jg-i0XlpcC&pg=PA198&hl=en

Goleman, Daniel, and Gregory Norris. "How Green Is My iPad?." The New York Times, April 04, 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2010/04/04/opinion/04opchart.html?_r=0 (accessed February 8, 2014).

h2g2, "Czochralski Crystal Growth Method." Last modified January 30, 2003. Accessed February 28, 2014. http://h2g2.com/edited_entry/A912151.

"How do they make Silicon Wafers and Computer Chips" March 05 2008. Web, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aWVywhzuHnQ.

"How it’s made Lithium Ion batteries" Recorded March 03 2008. Web, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HJrNCjVS0gk.

iFixit, "iPad Wi-Fi Teardown." Last modified 2014. Accessed February 25, 2014. http://www.ifixit.com/Teardown/iPad Wi-Fi Teardown/2183.

"IBM to recycle chips for solar panels." The New York Times, October 30, 2007. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/30/technology/30iht-ibm.4.8118325.html?_r=0 (accessed March 7, 2014).

Kumar, Aswin. Waste Management World, "The Lithium Battery Recycling Challenge." Last modified 2014. Accessed March 3, 2014. http://www.waste-management-world.com/articles/print/volume-12/issue-4/features/the-lithium-battery-recycling-challenge.html.

livescience, "Facts About Silicon." Last modified April 19, 2013. Accessed February 25, 2014. http://www.livescience.com/28893-silicon.html.

Lundstrom, Daniel, and Jan Yilbar. "Liquid Crystal Material." Accessed February 12, 2014. http://www.kth.se/fakulteter/_TFY/kmf/lcd/lcd~1.htm.

Satariano, Adam. "The iPhones Secret Flights from China to your Local Apple Store." Bloomberg, September 11, 2013. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-09-11/the-iphone-s-se

Shakhashiri, "Chemical of the Week: Aluminum." lecture., University of Wisconsin, 2008. http://scifun.chem.wisc.edu/chemweek/PDF/Aluminum.pdf.cret-flights-from-china-to-your-local-apple-store.html (accessed February 13, 2014).

"The Toxic 100 Air Pollutants." lecture., University of Massachusetts Amherst, 2013. http://www.peri.umass.edu/toxicair_current/.

Monica Hsu

Cogdell

DES 40A

13 March 2014

The Embodied Energy of an iPad

Apple Incorporated is an extremely successful American company that creates, develops, and sells electronics, computer software, and personal computers (Wikipedia, 2014). In one year, Apple sold 9.8 billion dollars of merchandise, which included one of their most popular items, the iPad (Business Insider, 2010). The iPad is a sleek line of tablet computers weighing in at 1.5-1.6 pounds per device. Some of its various capabilities include taking photos, surfing the web, playing games, reading books, and watching movies. Because it is such a phenomenon, an astounding 14.1 million iPads were sold in 2013 alone (TechCrunch, 2013). As consumers, we focus much on the great functionality and glory that products like the iPad provide for us. In result, we tend to overlook the intensive multi-step process, and how it affects the Earth. After much research, one can conclude that the amount of energy involved with the life cycle of an iPad is extremely high, despite Apple’s efforts to be environmentally friendly.

The first step in producing Apple’s iPad is acquiring the necessary raw materials that are used in the manufacturing process. Some of the most basic elements found in an iPad are aluminum, silicon, plastic, polycarbonate, glass, lithium-ion polymer, and polyurethane. In terms of mining raw materials, aluminum is one of the main elements in the iPad and is used for the back cover. According to Rain Forest Relief, Aluminum is one of the most destructive mining products in the world due to the large amount of waste it produces (Rain Forest Relief, 2014). For every ton of Aluminum produced, 20-30 tons of ore are mined and dumped. In addition, it takes an enormous amount of energy to extract the ore from the Earth. After the materials are mined, Apple relies on over 200 suppliers from all across the globe to cater to corresponding factories. Some of these suppliers are located in China, Ireland, Texas, Brazil, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Austria (Apple, 2014). According to Bloomberg News, Apple ships their materials and products using a family of long-range, wide-body, jet airliners referred to as Boeing 777s. They are one of the few jet airliners that can last a 15-hour flight without refueling. All in all, to consider the amount of energy that goes into acquiring raw materials, we must think about the energy that goes into mining the materials in combination with the energy it takes to transport them to factories. With the amount of iPads that are being sold each year, we can gather that the amount of energy used in this step alone is extremely high.

After acquiring necessary materials, iPads are manufactured and assembled in factories. Apple’s main manufacturer is a company called Foxconn located in Shenzhen, China (SFGate, 2014). To assemble the iPad, manufacturers put together a variety of specific parts. Some of the main components of the iPad include a thin film transistor liquid-crystal display, glass touch screen, aluminum backing, 3 silicon chips, main processing chip, NAND-type flash memory, and battery. Although the process is highly secretive, it is known that the production of the iPad is a combination of manpower and machine power. Assembly lines are utilized to make manpower highly efficient and machines take care of more precise tasks such as packaging. According to an article by New York Times, it takes approximately 100 kwhrs of fossil fuels to manufacture an electronic reading device like the iPad (New York Times, 2010).

Once the iPad is fully assembled and packaged, it is ready to take the multi-step journey to reach the hands of consumers. According to SFGate’s article, Where in the World is my iPad?, iPads travel to many places before they reach consumers or retail stores (SFGate, 2014). First, they depart from Foxconn’s factory in China and arrive in Anchorage, Alaska. Next, they make their way to Louisville, Kentucky. Finally, UPS ships the devices to households and local Apple retail stores all across the United States. Based on the research that I could retrieve, I came to the conclusion that a flight from China to the US takes approximately 7,200,000 MJs. In order to come to this conclusion, I gathered necessary information about how much it costs to fuel a Boeing 777 to make its way from China to the US. A 15-hour flight from China to the US using a Boeing 777 costs about $242,000 to charter and can carry about 450,000 devices (Bloomberg News, 2014). Fuel takes up half that cost, which brings it to $121,000. According to Ask.com, aviation fuel costs $2.81/gallon (since April 2013), which means it takes 43,060 gallons of fuel to fly 450,000 devices from China’s Foxconn factory to various locations in the US. It is not certain what type of Aviation fuel Apple uses in their Boeing 777s, but assuming they used BP Av gas 80, a common fuel used in Boeing 777s, we can say that the fuel used to carry iPads across the world contains 44.65 MJ/kg. Taking that into account, we can convert the 43,060 gallons to 163,197.4 kg and assume that it takes roughly 7,200,000 MJ to ship items from China to the US. In addition to the energy it takes to transfer raw materials, the embodied energy is already extremely high. However, the iPad’s life cycle has just begun.

When the iPad is in the hands of the consumer, it is in constant need for more energy to keep up with its usage. Because the iPad has so many features and is continuing to improve, consumers become more reliant on its functions and use it for longer periods of time. Om Malik, writer of the blog Gigaom, says that his iPad makes, “frequent visits to the electrical outlet – at least twice a day” (Gigaom, 2014). Apple claims that the latest model of the iPad offers up to 10 hours of battery life (Apple, 2014). According to research from Palo Alto, CA based Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), the cost of charging an iPad every other day for one year costs $1.36 (Gigaom, 2014). In terms of energy, the iPad consumes less than 12 kwh of electricity over the course of a year. Comparing this to a television that consumes 358 kwh a year, an iPad is relatively energy efficient. However, when you take into account the 14.1 million devices sold, the average energy used by all iPads in the market is about 590 gwh (Gigaom, 2014). Gigaom predicts that new iPads will consume about 65% more electricity per year. That is a strikingly large increase in the amount of energy consumed by iPads. Because of the increase in demand of iPads each year, Apple has made huge efforts to make their products more energy efficient. In the iPad specifically, Apple included an A6X chip, which is designed to allow the iPad to complete complex tasks without sacrificing its battery life. It is designed to be extremely powerful yet energy efficient. However, the collective energy use of an iPad worldwide is extremely high, which undermines the energy efficiency ideals that Apple attempts to instill in their company.

Although the iPad is designed to be long lasting and durable, they are oftentimes left behind due to damages or because they become outdated. Therefore, certain parts are recycled as a part of Apple’s overarching vision to be as environmentally friendly as possible. Although recycling is an effort to preserve the environment, it also takes a large amount of energy to deconstruct it to make it reusable. Aluminum is the main component of the iPad, with 125g of it in the product. To recycle aluminum, it must go through an intensive process in a recycling plant. First, it is transported to the recycling plant where it is sorted and cleaned using human power. Next, it goes through a melting process. Aluminum melts at an extremely high temperature of 1,221 degrees Fahrenheit (Wikipedia, 2014). The energy it takes to melt aluminum is approximately 52-56 MJ/kg. In addition, we must take into account the resources used to create this heat and the energy it took to retrieve it. Once the aluminum reaches 1,221 degrees Fahrenheit and melts, it is molded into large blocks called ingots. Finally, it is sent to mills to be rolled out and prepared to be re-used. Recycling the aluminum component of an iPad is only a part of the recycling process. In regards to the other components of the iPad, some of them are reused, modified, or resold. Apple also states that they partake in mechanical separation and shredding of recyclable parts. Ironically, recycling to benefit the Earth’s sustainability takes a great amount of energy, resources, and manpower.

Throughout the process of producing an iPad, waste is inevitably produced and requires energy to manage it. According to Apple, “[their] commitment to environmental responsibility extends deep into [their] supply chain” (Apple, 2014). Their commitment involves hazardous waste management, wastewater management, storm water management, air emissions management, and boundary noise management wherever Apple products are produced. In addition, Apple refrains from including hazardous materials in their products such as lead, mercury, cadmium, hexavalent chromium, and brominated flame-retardants (BFR) PBB and PBDE (Apple, 2014). Apple does a great job of associating minimal waste management with their product. However, as a researcher, it is almost impossible to get hard numbers and facts about how much waste is actually produced and how much energy it takes to minimize and manage that waste.

Through in-depth research, it is evident that Apple has made great efforts to reduce the amount of energy that is used to create and distribute the iPad. However, with consumer’s high demands and large amounts of iPads being distributed and used around the world, their energy consumption is still high. Considering the acquirement of raw materials, assemblage of the product, distribution and transportation, usage and maintenance, recycling processes, and waste management, it is evident that iPads require a lot of machine energy and manpower to exist. In large, we consume far more than our Earth can handle. If we were to continue using our resources unsustainably the way we do currently, we would need 5 more Earths to keep up with our consumption levels. Unfortunately, we only have one. In order to reduce energy consumption world wide, each individual must make an effort to rely less on products that require multiple processes and much energy to produce such as the iPad. In result, we will be more in tune with the Earth and how to utilize its sources more sustainably.

Works Cited

"Aluminium." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 03 Oct. 2014. Web. 10 Mar. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aluminium>.

"Aluminum." All About Aluminum. Rain Forest Relief, 2006. Web. 12 Mar. 2014. <http://www.rainforestrelief.org/What_to_Avoid_and_Alternatives/Aluminum.html>.

"Apple - Environment - Renewable Energy." Apple - Environment - Renewable Energy. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <https://www.apple.com/environment/renewable-energy/>.

"Apple - IPad Air - Features." Apple - IPad Air - Features. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.apple.com/ipad-air/features/>.

"Apple - Supplier Responsibility - Our Suppliers." Apple - Supplier Responsibility - Our Suppliers. N.p., n.d. Web. 12 Mar. 2014. <http://www.apple.com/supplier-responsibility/our-suppliers/>.

"Apple Inc." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 03 Nov. 2014. Web. 11 Mar. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apple_Inc.>.

"Apple Sold 33.8 Million IPhones, 14.1 Million IPads, And 4.6 Million Macs In Q4 2013." TechCrunch. N.p., n.d. Web. 12 Mar. 2014. <http://techcrunch.com/2013/10/28/apple-q4-2013-iphone-ipad-mac-sales/>.

Blodget, Henry. "15 Amazing Facts About Apple." Business Insider. Business Insider, Inc, 28 Oct. 2010. Web. 12 Mar. 2014. <http://www.businessinsider.com/15-amazing-facts-about-apple-2010-10>.

"Boeing 777." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 03 Dec. 2014. Web. 12 Mar. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boeing_777>.

"The Environment." Apple. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <https://www.apple.com/au/environment/our-footprint/#transportation>.

"How Green Is My IPad? Op-Chart." The New York Times. The New York Times, 03 Apr. 2010. Web. 12 Mar. 2014. <http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2010/04/04/opinion/04opchart.html?_r=0>.

"How Much Energy Does It Take to Power Those IPads? — Tech News and Analysis." Gigaom. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://gigaom.com/2012/06/21/so-how-much-does-it-cost-to-charge-an-ipad-every-year/>.

"What Materials Are Used to Make the IPad?" WikiAnswers. Answers Corporation, n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://wiki.answers.com/Q/What_materials_are_used_to_make_the_iPad#slide=2>.

"Where In The World Is My IPad? (AAPL)." SFGate. N.p., n.d. Web. 12 Mar. 2014. <http://www.sfgate.com/news/article/Where-In-The-World-Is-My-iPad-AAPL-2464279.php>