Design Life-Cycle

assess.design.(don't)consume

Aileen Yang

DES40A

Professor Cogdell

Raw Materials and Lifecycle of False Eyelashes

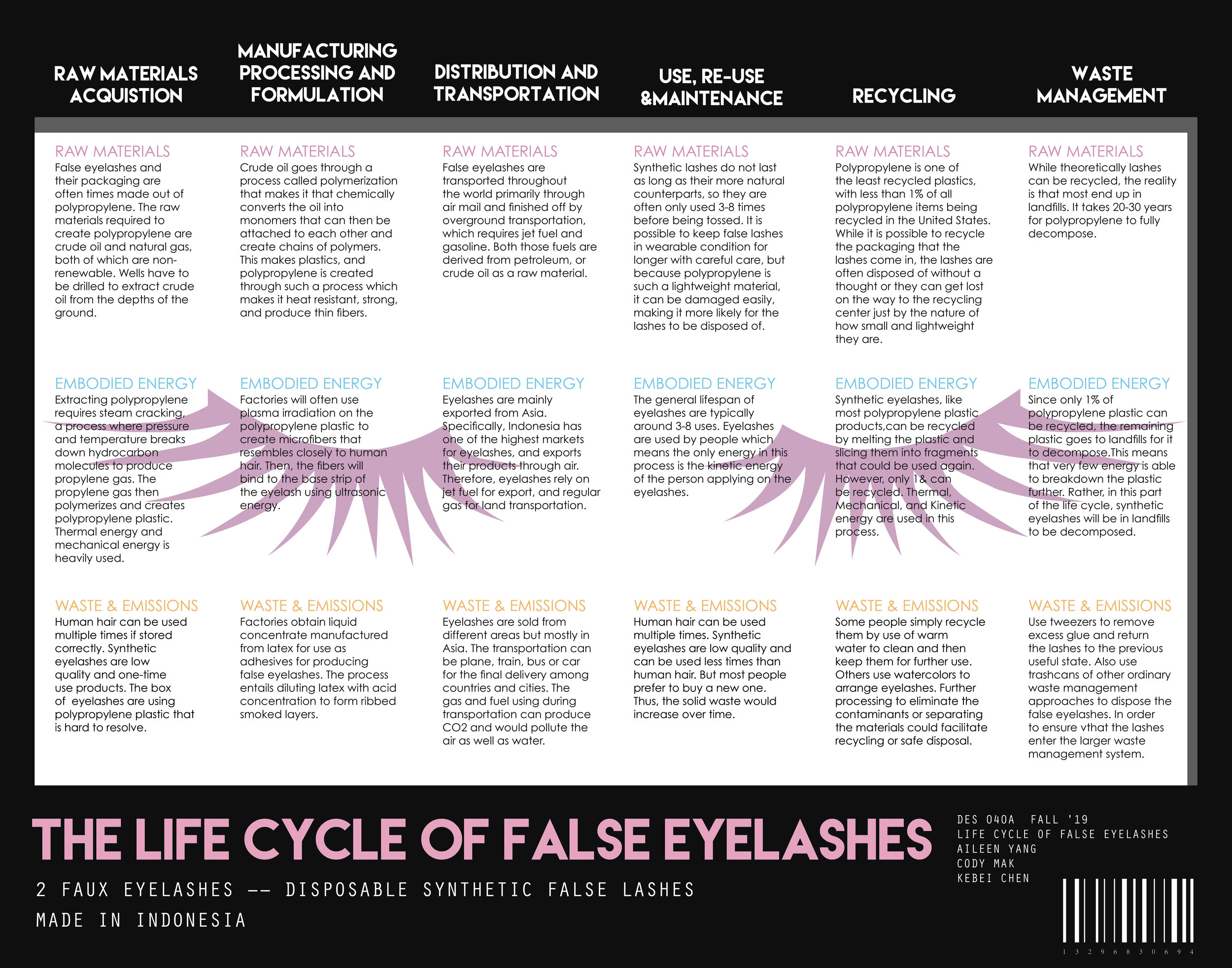

Throughout the past century, false eyelashes have become increasingly popular in the beauty world. Long eyelashes were mostly a trend for women throughout all of western history (with the exception of the 1400s), and women would go to extreme lengths to achieve the look of a full, luxurious set of eyelashes. Before false eyelashes, women could go through a procedure that transplanted hair from the head to the eyelash using a needle to thread the hair onto the lash line. This was extremely painful, yet still popular in cosmopolitan capitals. However, once Seena Owen dawned fashionable false eyelashes in the film Intolerance, the trend of gluing fake eyelashes took off. All the actresses started wearing them on set, and by the 1930’s false eyelashes were a staple in women’s beauty routine (Wright). Nowadays, false eyelashes come in a variety of styles, made with all sorts of materials, such as mink, fox fur, human hair, and synthetic plastics. The most common false eyelashes are often made of synthetic material, which makes the manufacturing, distributing, reusing, and recycling process difficult as the plastics do not last a long time and are detrimental to the environment. After researching raw materials, synthetic plastics will be discussed through the context of false eyelashes, where each pair is disposable and comes in polypropylene plastic containers.

The most common disposable false eyelashes and their packaging are made out of polypropylene plastic, and the raw materials used to create the plastic are crude oil and natural gas. The components of crude oil and natural gas are treated through a “cracking process” which converts it into hydrocarbon monomers, like ethylene and propylene (“Plastics”). With even more processing, crude oil can be converted into other monomers. Afterwards, these monomers are “chemically bonded into chains called polymers… yield[ing] plastics with a wide range of properties and characteristics” (“Plastics”). This process is called polymerization. Polypropylene plastic, specifically, is very resistant to chemical solvents, acids, and bases, and has a high melting point, which is why it was chosen as the material for packaging false eyelashes (LeBlanc). Polypropylene is also light in weight with a degree of strength, able to produce thin fibers, and cheap to produce, which is why it became a material of choice for the false eyelashes themselves (“Plastics”).

There is not a lot of information regarding the actual formulation and processing of false lashes from polypropylene to the soft, fluffy final product. A lot of the information seems to be missing outside of the fact that they are made out of plastic, making it difficult to understand the full scope of the lifecycle of false lashes. As a result, for the rest of the paper, I had to focus my research on polypropylene generally, and use the scarce information I could find on false lash creation to deduce the raw material usage and its effects.

Beauty products, including false lashes, are often shipped either directly to the consumer from the online retailer or shipped to a physical beauty retailer, such as Sephora or ULTA, where consumers can shop and buy products that they want. Oftentimes, orders are shipped via USPS First Class Mail Shipping by retailers (“Shipping: Makeup, Cosmetics Shipping Policy”). Oftentimes, First Class Mail Shipping means the bulk of transporting the item is done by aircraft, then finished off by ground transportation to deliver to the consumer (“What is Air Mail?”). This means that jet fuel and gasoline would be needed in order to deliver false eyelashes around the world. Both jet fuel and gasoline are manufactured from petroleum, which is also crude oil (Heminghaus, Greg, et al.). Crude oil is nonrenewable and can be detrimental to the environment, especially when there are oil spills. However, there are new developments in science by researchers that are looking for new potential alternative fuels. For example, coal liquefaction is a technique that could be implemented to make jet fuel, but it has only been tested in the laboratories and is currently not in use commercially (L.M Balster, et. Al). Therefore, in the near future, there can be other raw materials involved in the transportation and shipping of false lashes.

In order to apply false eyelashes, the user must apply some adhesive, or lash glue, to stick the eyelash to the lash line. This introduces small, trace quantities of new raw materials onto the false eyelashes. Popular lash glues are often made of water, cellulose gum, rubber latex, and small amounts of sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate, ammonium hydroxide, and formaldehyde (“Eyelash Adhesive - DUO”). Another popular ingredient that other lash glue brands use is ethyl cyanoacrylate, which is the same chemical used in nail glue (“What Are The Sky Glue Ingredients?”). Sometimes, the lash glue is included in the kit of false lashes for convenience, often packaged in a small, malleable plastic tube ready for the user to squeeze out. The lash glue is often left on the false eyelash when disposed of, introducing new raw materials to the product.

False eyelashes are usually considered disposable, and ones created out of synthetic materials even more so because of their cheap and affordable price point. Typically, synthetic lashes last around 3-8 uses (“How to Get the Most Use Out of Your Falsies”). Depending on how the user takes care of the lashes and the frequency of use, each pair can last a couple of days to a few weeks. A more careful user that takes the lashes off slowly and puts them back in the packaging to keep the shape of the lash is more likely to have lashes that stay intact for longer. However, due to the nature of polypropylene, lashes are just not built to be reused many times. The plastic is cheap and the fibers can bend very easily, leaving the lashes in undesirable shapes. Ultimately, the lashes are disposed and replaced very quickly. No new raw materials are introduced in this stage.

There is not much information on the recycling of false eyelashes specifically, but there is information about polypropylene recycling. Despite polypropylene being one of the most common types of plastic used for packaging, the American Chemistry Council estimates that less than 1% of the all polypropylene used in the United States is recycled (LeBlanc). This includes false eyelashes and their packaging. Because of its small size and light mass, it is possible that many lashes get lost before being processed at a recycling plant. There is also little labeling or direction on how to recycle or dispose of the lashes, so it is possible that the consumer may just throw it in the trash, where it goes to a landfill to decompose. In a landfill, polypropylene takes 20-30 years to fully decompose (LeBlanc). For something that is considered so small that it is disposable, in large quantities it has a detrimental effect on the growing problem of plastic pollution in the world and the attitudes toward single-use plastics. There are no new raw materials that are introduced in this phase, rather, polypropylene just continues to slowly decompose on its own, taking decades before even the smallest package or eyelash will fully disappear.

Throughout this project, I realized that there is a clear lack of transparency in the beauty industry, specifically involving false lashes. There was no information about where the synthetic materials were sourced from, and it was difficult to even pinpoint that the synthetic material that the eyelashes were created from was polypropylene. I also could not find anything regarding how plastic could be converted into eyelashes, or how the actual false eyelashes were constructed. There are no answers for how the plastic is treated in order to form thin, fluffy lashes and therefore the raw materials that can possibly be used in that step cannot be taken into account in this lifecycle assessment. However, what is most disappointing is that there was no information about the disposal of eyelashes or boxes. While the boxes are generally marked as recyclable, there are no explicit instructions on how to dispose of the lashes. This means the companies that create false eyelashes do not take into account the end of the lifecycle of their products, only the beginning. There are several videos and articles online by independent creators that give people ideas on ways to repurpose their eyelashes, but it should not be up to the consumer to figure out what to do with the waste that companies produce.

Even with the information that is public, it is still clear that false eyelashes and their packaging is harmful to the environment. By having having a few pairs of eyelashes, or even single pairs of eyelashes, packaged in bulky, thick polypropylene boxes is unethical. Not only is polypropylene made out of crude oil and natural gas, which are nonrenewable resources that can eventually be depleted. Fracking for crude oil is also detrimental to the environment as it can cause oil spills, ruining soil and water around it. It can also induce earthquakes as it requires high pressure to extract oil and gas from the rocks (Horton, Melissa). To make false lashes more sustainable, there would have to be a large shift in the way that the beauty industry thinks about lashes and design. Companies would have to take into consideration what happens after the lashes are used, and what steps are necessary to take to make the packaging more sustainable, such as implementing a recycling program or using a different material.

Works Cited

“Eyelash Adhesive - DUO.” Sephora, www.sephora.com/product/eyelash-adhesive-P266812.

Hemighaus, Greg, et al. Alternative Jet Fuels. Chevron Corporation.

Horton, Melissa. “What Are the Effects of Fracking on the Environment?” Investopedia, Investopedia, 19 Nov. 2019, www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/011915/what-are-effects-fracking-environment.asp.

“How To Get The Most Use Out Of Your Falsies.” Bustle, www.bustle.com/articles/142766-how-many-times-you-can-reuse-false-lashes-plus-5-ways-to-make-them-last-their.

LeBlanc, Rick. “Polypropylene Recycling - An Introduction.” The Balance Small Business, The Balance Small Business, 9 May 2019, www.thebalancesmb.com/an-overview-of-polypropylene-recycling-2877863.

L. M. Balster, et. al. “Development of an Advanced, Thermally Stable, Coal-Based Jet Fuel”, Fuel Processing Technology.

“Plastics.” Lifecycle of a Plastic Product, American Chemistry Council, plastics.americanchemistry.com/Lifecycle-of-a-Plastic-Product/.

“Shipping: Makeup, Cosmetics Shipping Policy.” Beauty For Real, www.beautyforreal.com/pages/shipping.

“What Are The Sky Glue Ingredients?” Sky Glue, 9 May 2018, skyglue.store/blogs/sky-glue/what-are-the-sky-glue-ingredients.

“What Is Air Mail? ” Stamps.com Blog - Tips and Info on USPS Shipping Software, 10 June 2017, blog.stamps.com/2017/06/09/what-is-air-mail/.

Wright, Jennifer. “A True History of False Eyelashes.” Racked, Racked, 7 Oct. 2015, www.racked.com/2015/10/7/9457395/a-history-of-false-eyelashes.

Cody Mak

DES 040A

Professor Cogdell

Energy Life Cycle of False Synthetic Eyelashes

Synthetic eyelashes have been frequently used and favored by consumers in the cosmetic industry. These eyelashes provide a quick and simple way for a person to enhance their natural eyelash length. Behind the process of making these lashes, certain energy forms and materials were used. Ranging from ultrasonic energy, plasma radiation, kinetic, and mechanical energy, these embodied energy in the life cycle were all used in the process of producing eyelashes. Technology and machineries have advanced such that these energy forms are energy efficient and environmentally produceable. Through my research of embodied energy of synthetic lashes, I have discovered that there are a variety of energies used to produce synthetic eyelashes, utilizing its environmental and energy efficiency in order to deliver mass bulks of eyelashes from manufacturers to consumers. Even as a simple product, these embodied energies show a significant amount of complexity in the manufacturing process of synthetic eyelashes, and can range in the process of raw material acquisition and transportation, dealing with environmental issues and the limited reusability/recycling aspect of the product.

Since synthetic eyelashes have been one of the more purchased items in the cosmetic realm, I dedicate this research to show how much energy is used throughout the life cycle. These traces begin from extracting and manipulating raw materials such as polypropylene plastic to create the products and to be delivered for consumers. There are very few studies that heavily goes into detail about these disposable synthetic eyelashes. The purpose of the study is to extrapolate information of the whole life cycle and give a general idea of how the energy is used and recycled throughout the process.

Firstly, I found that synthetic eyelashes are made of synthetic fibers that are derived from polypropylene plastic. Polypropylene is a material produced by a chemical process from using natural polymers such as cellulose, starch, natural gas, and other proteins. Specifically, it relies on a chemical polymerization of propylene gas at around 160 celsius or 320 Fahrenheit (“Polypropylene”). This polymerization of propylene gas comes from steam cracking, a process where it relies on breaking down hydrocarbon molecules by pressure and heat, typically around 1500 degrees Fahrenheit. In the steam cracking process, thermal energy and kinetic energy of gasses are heavily relied on the production of polypropylene plastic, as the pressure and temperature changes are able to alter molecular structures (“Polypropylene”). In fact, China is the lead acquisition for polypropylene production, and is also one of the main countries to export synthetic lashes to consumers. China produces 20.2 million tons of polypropylene, which shows how much energy is used in the acquisition of the material used in many products (“Polypropylene Production Capacity, Market and Price.”).

After extracting polypropylene plastic, there are various forms of creating the synthetic lashes such as ultrasonic energy, plasma radiation, kinetic energy, and mechanical energy. First, the synthetic eyelashes are made of small synthetic fibers. These synthetic fibers are created by plasma irradiation of polymers. Plasma irradiation creates small particles on a fiber where it creates small spaces and openings between individual hairs having between 0.03 and 1 microns through using 1 and 200 square micron projections (Akagi). After creating these fibers, these polymers would have synthetic hair similar resembling real eyelash hairs. Moreover, plasma irradiation relies on the alteration of atomic particles to create the individual fake hair, rather than relying on high thermal energy to create individual strands of hair.

After the individual hairs are created, it is attached to the base strip. During this process, manufacturers use ultrasonic energy to bind the hairs on the base strip using rapid molecular movements. Ultrasonic energy is the mechanical energy that moves particles in an item using sound vibrations, and is often used in the production of products and in surgical medical purposes. The mechanical energy of the ultrasonic energy is an alternative for any adhesive usages such as glue, and relies on vibrations to bind the hair and the base strip. The frequency required to produce an ultrasonic treatment has to be greater than 20kHz (Osher 2). Additionally, ultrasonic energy is a secondary energy source, such that it relies on electromagnetic energy to transmit higher frequencies to produce the ultrasonic effect (Osher 4). It is important to note that ultrasonic energy has been scientifically studied because of its great environmentally friendly usage. Since ultrasonic energy relies on sound energy rather than thermal energy, the solidification or binding of mediums are more energy efficient and safe (Riedel). Adhesions of plastics can involve using heat and could potentially have a higher fire risk since polypropylene plastics have a high melting point of around 130 degrees celsius (Mechanisms). Therefore, ultrasonic method binds together the base strip and the synthetic hairs to produce false eyelashes more efficiently and safely in terms of energy and environmental safety.

Transportation of false eyelash products mostly rely on fuel as their main energy source. Although I could not find an actual company with specific resources to transport false eyelashes, I did find that most eyelashes are exported from Asia to America. Specifically in Asia, Indonesia has been one of the more prominent countries to push out exports of false eyelashes due to its massive global success in manufacturing false eyelashes (Liem). A shipment export data of Indonesia shows that Indonesia ships around 13,560 quantities of eyelashes per export through air (Drive). Since the exports travel by air, I have collected information about how much jet fuel is used in the transportation of products. Boejing aviation export requires around 36,000 gallons of fuel to export products on a 10-hour flight (Contributor). Although it was hard to find the specific fuel amount for eyelash transportation, we can generalize that transportation of these products requires a lot of jet fuel to deliver a bulk of synthetic eyelashes. Since this research is focused on the energy life cycle for general synthetic eyelashes, it is ultimately up to certain cosmetic brands to decide on the amount to export eyelashes after production, which could vary in different fuel consumption. Finding information relevant for transportation of the product to consumers was rather difficult. I could not find specific data pertaining to how much means only a small amount of synthetic eyelash products could be delivered under a limited amount of fuel supply (FedEx 83). Even though there are limited sources that addresses specifically the embodied energy in the transportation portion of the life cycle, the research confirms that fuel is the main energy source to drive mechanical and kinetic energy of transportation vehicles such as planes and trucks to deliver false eyelashes.

Synthetic eyelashes are designed to provide a quick and simple way to glamor an appearance. However, synthetic eyelashes are cheap and have limited usages before it becomes unwearable. On an average, synthetics eyelashes last around 3-5 uses before it could no longer adhere to the eyelashes (Barlow). Since synthetic eyelashes are made of polypropylene plastic, it is hard to recycle the product. Approximately only 3% of the polypropylene plastic can be recycled, and it takes about 20-30 years to decompose. According to Le Blanc, the recycling starts by collecting, cleaning, and reprocessing the recycled polypropylene and places the polypropylene product in an extruder in 4,640 degree Fahrenheit and sliced in tiny fragments (LeBlanc) . During this process, thermal energy and mechanical energy is used to purify and slice the recycled polypropylene plastic into pieces that could be used again for new products. The remaining polypropylene plastic would end up in our ecosystem, further filling up land and oceans.

During this research, we conclude that the creation of synthetic eyelashes heavily relied on a variation of kinetic energy, thermal energy, and mechanical energy. Most of the information about the energy in the manufacturing processes are cited from prototypes and inventions portraying techniques to create eyelashes. However, finding sources of specific companies who uses these methods were difficult to locate. It is important to consider how the majority of the research for embodied energy are mainly focused in the material acquisition and manufacturing process. Energy sources pertaining to other categories such as transportation, recycling, and waste management have less relevant studies to portray a clearer picture of embodied energy in the life cycle of the eyelashes. Rather, these sources paint a general overview of the embodied energy for synthetic lashes.

Overall, I think the most challenging part of the research was finding important resources that pertain specifically for synthetic eyelashes. However, I approached this research by analyzing specific components of the eyelashes and researching their individual embodied energy in every aspect. For example, since the synthetic eyelashes are made of mostly polypropylene plastic, I decided to look through the energy process of extracting the polypropylene plastic as a raw material, and I researched how the recycling/waste management of plastics is managed. As a result, those findings could generalize how synthetic eyelashes are created, recycled, and decomposed. Finding embodied energy in transportation was a challenge because I was unable to find information regarding delivering eyelashes to retails. However, I did find that most eyelashes export by air, and is delivered to retails on land. With this information, I connected to how much fuel is used per air travel, and how little each box of eyelashes can be delivered. Interestingly, there were more information about the embodied energy in the production process. As I browsed through google scholar, I discovered different inventions and factory methods to create the synthetic eyelashes by using different energy processes such as ultrasonic treatment and plasma irradiation. Even though synthetic eyelashes is a simple product, this research shows the complexity and energy used in almost all steps of the life cycle. I enjoyed learning about chemical processes behind products, and how much kinetic, thermal, and mechanical energies are involved in the making of eyelashes. From material acquisition, to recycling the eyelashes, the embodied energy in synthetic eyelashes show a great importance to understanding the amount of environmental effect and energy usage in all stages of the life cycle in the product.

Works Cited

Akagi, Takao, et al. "Synthetic fibers imparted with an irregular surface and a process for their production." U.S. Patent No. 4,451,534. 29 May 1984.

Barlow, Eliza. “Are False Eyelashes Single-Use or Can They Be Reused? [Revealed].” False Eyelashes Reviews, Alleyelashes, 5 July 2019.

Contributors, HowStuffWorks “How Much Fuel Does an International Plane Use for a Trip?” HowStuffWorks Science, HowStuffWorks, 28 Jan. 2015.

Drive, Info. “Date.” False Eyelashes Import Data India, Customs False Eyelashes Import Data & Price, 29 Nov. 2019.

FedEx. “FedEx Ground Package.” Material Restrictions, Apr. 2019.

LeBlanc, Rick. “Polypropylene Recycling - An Introduction.” The Balance Small Business, The Balance Small Business, 9 May 2019,

Liem, Mita Valina. “Indonesia Firm Churns out Fake Lashes to the World.” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, 12 Dec. 2007.

Osher, Benjamin B. "Method of making artificial eyelashes using ultrasonic means." U.S. Patent No. 3,447,540. 3 Jun. 1969.

“Polypropylene Production Capacity, Market and Price.” Plastics Insight, 2019,

“Polypropylene.” The Polymer Science Learning Center, 2003, pslc.ws/macrog/pp.htm.

Riedel, E., et al. "Ultrasonic treatment: a clean technology that supports sustainability in casting processes." Procedia CIRP 80 (2019): 101-107.

Staff, Creative Mechanisms. “Everything You Need To Know About Polypropylene (PP) Plastic.” Everything You Need To Know About Polypropylene (PP) Plastic, 4 May 2016.

KEBEI CHEN

DES 40A

Professor Cogdell

Waste and Emissions of False Eyelashes

False eyelashes are among the false hair products (FHPs) manufactured from human hair and synthetic fibers. Sometimes, false hair products combine both human hair and synthetic materials. The demand for such products continues to cause a significant environmental impact due to the emissions of wastes. The pressure is also mounting on operators in the false hair industry to find a way of reducing production and supply of human and synthetic hair to reduce the increasing environmental impact. The purpose of this research paper is to investigate the emissions and disposal of waste according to the lifecycle of fake hair products. The false hair product industry comprises of a wide range of products such as eyelashes, eyebrows, full and partial wigs, toupees, weaves, toppers, and a variety of extensions (Wilson et al. 235). Whereas companies can provide human hair products to the growing global market, the current supply of quality of products made from natural human hair is few than the demand. However, synthetic materials for manufacturing fake human products are readily available. Environmental researchers thus warn that the growing global manufacturing of polymers (chemical compounds for making synthetic false hair products) produces significant quantities of waste material that cause major environmental issues.

Artificial eyelashes come in three categories, including human hair, synthetic and mink fur lashes. Human hair eyelashes are the best quality products made from authentic natural hair, and they imitate the look of a person's lash. Although they are expensive than their synthetic counterparts, people find them to be comfortable, long-lasting and can seamlessly merge with the individual's hair. This particular type of lashes has minimal environmental danger because a person can use them multiple times if stored in the recommended place. However, synthetic eyelashes are entirely the opposite of human hair lashes. Manufacturers use human-made materials that pose a significant danger to the environment, such as rubber and some recyclable materials (Wilson et al. 235). While synthetic eyelashes are cheaper, most of them are usually of lower quality; hence, they are one-time use products. The users dispose them quickly because using them longer may damage the eyes and cause the eyelids to droop. The false hair products industry is currently under the spotlight due to the recent increase in the varieties of false hairs, most of which negatively affect the environment. Besides, manufacturers of these products are not courteous about the environment; thus, they repeatedly lead to the escalation of the environmental risk.

According to Abdel-Shafy and Mansour (1275), emission and disposal of solid waste remain a callous and widespread problem both in rural and urban places in most developed and developing states. Most of these nations face a significant challenge regarding the collection and disposal of municipal solid waste (MSW), especially in urban settings. The generation of solid waste has been escalating over the years, making it difficult for most small and large cities across the world to manage mainly due to the low municipal budget. Studies also acknowledge that a lack of understanding of diverse factors that affect the waste disposal process other than the high costs continue to hinder the effective management of solid waste (Abdel-Shafy and Mansour 1276). Various studies attribute the escalating amount of solid waste around the world to human factors such as increasing population, the rapid development of urban centers, flourishing economy, and growing standard of living in both developed and developing states. These factors also affect the quality of solid waste generated and disposed to the environment, for instance, companies in the false hair industry.

The production, processing, and formulation of false eyelashes is a multistep process that combines chemical and physical procedures. After obtaining all the materials, manufacturing and processing entail converting 10% of the latex into a liquid concentrate and removal of water to increase the content of rubber to 60% (Fisher, Joseph and Matthew 66). The process uses creaming or centrifugal force to evaporate the excess amount of water. The next step involves the addition of a chemical agent to the latex to make particles of the rubber to swell and rise to the surface of the liquid concentrate. The processed product is ready for transportation to factories where they use it as adhesives or coatings. Another danger that emerges in this stage is due to the use of acid to make dry latex. Coagulation involves adding acid to the liquid concentrate in a large extrusion dryer to eliminate water and remain with crumb-like materials (Fisher, Joseph and Matthew 66). The factories then compact the dried rubber into bales and crates ready for transportation. Formulation and processing also pose a considerable danger due to the use of chemicals to produce sheets. The process entails diluting latex with acid concentration to form ribbed smoked layers. The role of the acid is to make rubber particles to gather on the surface of the watery serum. The acid also facilitates rapid coagulation of jellylike rubber, which stays undisturbed for a period between 1 to 18 hours then pressed together using rollers to form then sheets. The pressing stage assists in eliminating excess liquid to create ribbed sheets. The ribbing is necessary to accelerate drying.

False hair manufacturing factories obtain the different forms of latex for use in making final eyelashes that they sell to users around the world. For instance, factories obtain liquid concentrate manufactured from latex for use as adhesives for producing false eyelashes. The final phase of creating artificial eyelashes involves the use of synthetic and natural fibres, for example, human hair. They mount the hair on thin fabric strips. The adhesive often is a blend of cellulose gums, concentrate of rubber latex, and casein (Fisher, Joseph and Matthew 69). The formulation of adhesives makes the eyelashes easily removable by peeling off and prevents irritation.

The false hair industry utilizes various distribution channels to deliver false eyelashes to the market. The three common distribution channels that major industry players like the House of Lashes use are convenience stores, online, as well as hypermarkets and supermarkets. For instance, in 2018, distribution through convenience stores alone accounted for 50% of the global market share (Grand View Research). Convenience stores channel comprises of options such as drug, department, and specialty stores. Although online business is booming currently, consumers of false eyelashes prefer buying them from physical locations like convenience stores because most of them are very particular with the shape, size, and design. Specialty stores play a crucial role in influencing emissions and disposal by offering users some expert advice to minimize cases where customers buy eyelashes that do not fit their taste hence disposed quickly (Grand View Research). Providing expert advice regarding use and care also helps to reduce the amount of waste generated instantly.

Manufacturers of products like eyelashes use specialized ingredients that require special storage and particular care during transportation to prevent adverse incidents that may happen because of bad weather such as high temperature and humidity as well as unique lighting (Jurczak). The logistics chain enforces rules of conduct for governing behaviors of suppliers and shipping companies. Mandatory requirements in logistics ensure that products meet the required standards to be legal and fit for users and to the environment (Jurczak). For instance, House of Lashes has a list of mandatory rules that guide its distribution and shipping activities in the U.S. and overseas. An example is that customers must accept packages delivered by particular carriers, UPS and USPS, that House of Lashes chooses. Priority products that require urgency, as well as urgently orders (delivered between 1 to 3 days), use transportation channels that ensure the goods reach destinations on time.

Eyelashes manufactured from human hair hinder effective disposal and solid waste management because users do not consume the hair. For instance, a person would only put on the eyelashes for a certain period then throw them away to get a new pair. For that reason, no use of such eyelashes decreases the amount of solid waste as it always gets its way back into the waste disposal systems (Gupta 10). As the demand for eyelash extensions continue to increase, the solid waste would also increase over time. However, three types of uses could help recycle eyelashes made from natural human hair. In type 1 use, recycling of the hair is possible with the help of fertilizer, which facilitates decomposition of the strands to return the elements into cycles of nature (Gupta 10). In type 2 use, recycling occurs by reuse. The hair strands remain intact when in use to allow further reuse or recycling for the same or different purposes. Type 3 use involve applications that contaminate the hair with pollutants that do not leave the hair intact for recycling. However, further processing to eliminate the contaminants or separating the materials could facilitate recycling or safe disposal. Some people simply recycle them by use of warm water to clean and then keep them for further use. Others use watercolors to arrange eyelashes for reuse.

Cleaning, storage, and reusing false eyelashes is one approach that users could use to manage solid waste. Most people dispose their false eyelashes after use, but there are various tips that one could do to manage the waste at home. For instance, a person could use tweezers to remove excess glue in case she did not apply mascara on them. Tweezers help to return the lashes to the previous useful state. In the event she applied mascara, eye makeup removers could help to clean the lashes gently and store them for later use. However, individuals could use ordinary waste management approaches to dispose the false eyelashes, for example, trashcans. Disposing them together with other solid waste ensures that the lashes enter the larger waste management system.

With the escalating innovation patterns, people would continue to develop new beauty products, most of which could have adverse environmental effects. False eyelashes, for example, are rapidly becoming a necessity for most women around the world. Despite their smaller size, the growing use suggests that there could be a looming major environmental concern. Manufacturers, however, try to use technology-enabled methods to minimize emissions during processing and formulation. Distribution and transportation also involve the use of advanced techniques that limit instances of environmental pollution. The problem arises in the final stage when the false eyelashes reach the consumer. Users who may not be conversant with waste management and courteous about environmental conservation may continue to harm themselves and the environment. Hence, it is essential to encourage sustainable production and use of false eyelashes to ensure resilient waste management.

Bibliography

Abdel-Shafy, Hussein I., and Mona S.m. Mansour. “Solid Waste Issue: Sources, Composition,

Disposal, Recycling, and Valorization.” Egyptian Journal of Petroleum, vol. 27, no. 4,

2018, pp. 1275–1290. doi:10.1016/j.ejpe.2018.07.003.

Fisher, Alexander A, Joseph F. Fowler, and Matthew J. Zirwas. Fisher's Contact Dermatitis.

Phoenix, AZ: Contact Dermatitis Institute, 2019. Print.

Grand View Research. “False Eyelashes Market Size: Global Industry Analysis Report,

2025.” False Eyelashes Market Size | Global Industry Analysis Report, 2025, Sept. 2019, https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/false-eyelashes-market.

Gupta, Ankush. “Human Hair ‘Waste’ and Its Utilization: Gaps and Possibilities.” Journal of

Waste Management, vol. 2014, 2014, pp. 1–17., doi:10.1155/2014/498018.

Han, Kyu Sang, and S. U. N. G. Siyong. "False eyelash packaging." U.S. Patent Application No.

14/645,920. https://patents.google.com/patent/US20160264334A1/en

Kim, Yong Se, et al. "False eyelashes and manufacturing method therefor." U.S. Patent

Application No. 14/363,274. https://patents.google.com/patent/US20140332025

Mcgivern, Barbara J. "False eyelash container and curler." U.S. Patent No. 3,333,593. 1 Aug.

1967. https://patents.google.com/patent/US3333593

Jurczak, Michał. “Transport and Logistics of Cosmetics, or What Is the Point of Traceability of

Expensive and Fragile Loads?” Website and Forum for Transport and Logistics, 9 Oct.

2019, https://trans.info/en/transport-and-logistics-of-cosmetics-162546.

Ray, Sebastian. "Shaping device for artificial eyelashes." U.S. Patent No. 3,200,823. 17 Aug.

1965.

Udes, Benjamin. "False eyelashes with woven edges." U.S. Patent No. 3,561,458. 9 Feb. 1971.

https://patents.google.com/patent/US3561458A/en

Wilson, Nicky, et al. “Capturing the Life Cycle of False Hair Products to Identify Opportunities

for Remanufacture.” Journal of Remanufacturing, vol. 9, no. 3, Nov. 2019, pp. 235–256.,

doi:10.1007/s13243-019-0067-0.

.