Design Life-Cycle

assess.design.(don't)consume

Michelle Marin

Christina Cogdell

Design 40A

15 March 2016

Materials Used in the Life Cycle of a Tampon

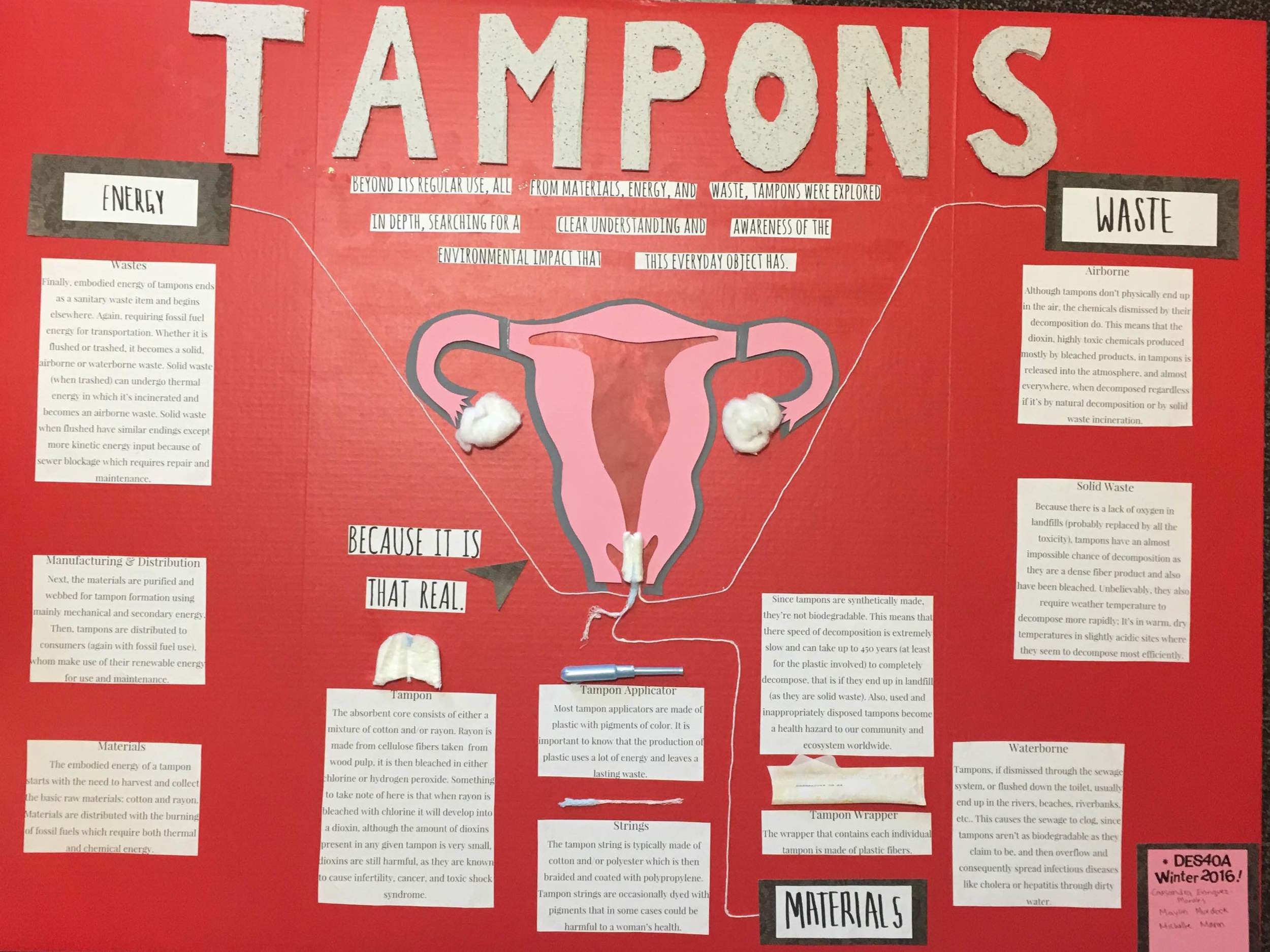

Every month about half of the adult population experiences a period as a part of their menstruation cycle. This monthly event inevitably requires women to invest in feminine hygiene products, one of which is a tampon. Tampons have become especially popular in industrialized countries “Approximately 55% of white women of reproductive age, 31% of Black women, and 22% of Hispanic women report using tampons.” The average woman uses about 11,000 tampons in her lifetime, that number makes it evident that tampons are a very important personal product. Because tampons have such a big role in the lives of women it is important to know what role they play in our world. As consumers it is our duty to understand what it is we are consuming especially since “ major companies are not obliged to disclose these ingredients – in the US this is because the food and drug administration classes feminine hygiene products as medical devices, not personal care products “ This paper will cover the materials used in the five main aspects of a tampon and will also include the impact of those materials on the environment and personal health. A package of tampons is composed of the absorbent core(throughout this paper I will refer to this as the tampon), the string that is used in the removal of a tampon, the tampon applicator which is used in the application of a tampon, the wrapper that holds each individual tampon, and the box that holds all of the tampons. It is important to consider the impact of the materials used in the production of a every part of a tampon including the tampon, string, plastic applicator, the wrapper, and packaging, on the environment and on women’s health. Tampon and Tampon String

The production process of the tampon begins with the cultivation of cotton and the creation of rayon. Many companies use either cotton or rayon and sometimes a blend of the two to create the absorbent core. Cotton is farm grown and taken from farms to production factories to be used in the production of tampons. Rayon consists of “cellulose fibers derived from wood pulp” This material is used because “Rayon is a highly absorbent fibre which rapidly absorbs menstrual blood”, and also because it is a relatively cost effective material. Because rayon is derived from wood pulp, it must purified so that it is free of pesticides and other potentially harmful chemicals used in its creation. To purify rayon the cellulose fibers are bleached in either chlorine or hydrogen peroxide. Chlorine bleached paper often produces dioxins which are very harmful to the human body , so as a result tampon manufacturers have begun to use different production methods to minimize the production of dioxins. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration reports two main processes used to purify rayon. The first process is referred to as the elemental chlorine-free bleaching process and it “[does] not use elemental chlorine gas to purify wood pulp”, however this process “can theoretically generate dioxins at extremely low levels, and dioxins are occasionally detected in trace amounts in mill effluents and pulp. In practice, however, this method is considered to be dioxin free.” The other process the FDA mentions is called the “Totally chlorine-free” process and it relies upon “the use of bleaching agents that contain no chlorine.” This method is considered dioxin free because it “[uses] hydrogen peroxide as the bleaching agent” in the place of chlorine.

Tampons and many other feminine hygiene products used by industrialized nations are predominantly disposable, so as a result tampons are not reusable or recyclable and they create an enormous amount of waste “the average woman throws away up to 300 pounds of feminine hygiene related products in a lifetime.”. In addition to the amount of waste produced it takes a single tampon up to six months to decompose, this does not include the applicator or the packaging. The absorbent core itself, specifically “the cotton fibers used in the production of tampons contributes 80% of their total impact. The processing is resource intensive as the farming of cotton requires large amounts of water, pesticides and fertilizer.” Tampons impact more than just landfills, when flushed they can create serious problems for marine life. They not only pollute ocean waters by releasing dioxins and human waste but they can also cause suffocation or the death of marine animals if they ingested. The byproducts produced during the creation of tampons and present during their use and even after their disposal may be “negligible” when considering each tampon individually, but when we take into consideration the amount of tampons used within a woman’s lifetime the amount of toxic waste is paramount.

Consumers should be aware of the risks that their products entail. As mentioned before dioxins are present inside of a tampon because the rayon used to make tampons must undergo a “chlorine bleaching process that is used to make theses products look “cleaner” or more sanitary” which in turn produces dioxins. Rayon is used in tampons because it is “a highly absorbent fibre which rapidly absorbs menstrual blood but at the same time can also dry out the natural protective mucous lining of the vagina.” The absorbent core has the largest impact on a woman’s health because the vagina is one of the most absorbent parts of the human body. According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration “the detectable limit of this assay is currently approximately 0.1 to 1 parts per trillion of dioxin.” So while this number is very small it is also important to remember that this is what might be detected in a single tampon. Let’s consider again how many tampons a single woman can use within her lifetime, the average is 11,000. When we multiply one part per trillion by 11,000 we get 1.1e-8. While this amount is very small it is important to note that it is present and that it varies depending on each woman’s individual preferences. “Trace quantities of dioxin found in tampons aren’t in and of themselves the issue, it’s the overall exposure and build up that the use of chlorine-bleached and rayon based tampons adds that’s the problem.” Many health problems have been caused by dioxins, a dioxin is an extremely harmful chemical compound that is often produced in the manufacturing of certain products, typically produced from bleaching paper products with chlorine. They are known to cause infertility, cancer and seem to have a correlation with toxic shock syndrome. Dioxins can be found in meat, dairy products and according to the FDA they can also be a result of “other environmental sources”. Since dioxins are so harmful and so evident in our lives already than we as women can not afford to increase the possibility of obtaining a severe illness by knowingly choosing to consume something that cause harm to our bodies.

Tampon Applicator

Tampon applicators are made up of plastic and pigments to add color. The production of plastic for a tampon applicator “requires a lot of energy” The process virtually follows the general plastic production process. Plastics are made of “natural products such as cellulose, coal, natural gas, salt and of course, crude oil” Crude oil is a very important part of the production of plastic, it “is a mixture of thousands of thousands of compounds.” and “it must be processed” to be useful in the production of plastic. First crude oil is separated into smaller portions, those portions are then mixed with hydrocarbon chains. There are “two major processes used to produce plastics are called polymerisation and polycondensation, and they both require specific catalysts. In a polymerisation reactor, monomers like ethylene and propylene are linked together to form long polymers chains.” Even so there are still many different variations of plastics, however they can still be categorized into two main categories which are “thermoplastics (which soften on heating and then harden again on cooling)” and “thermosets(which never soften when they have been moulded)”. The production of plastic is very long and it requires and it immense amount of energy “As production of these plastics requires a lot of energy and creates long lasting waste”

Similar to the absorbent core, the plastic applicator produces a lot of waste and takes a toll on the environment as well. The rate at which a plastic applicator decomposes can be “centuries longer than the lifespan of the woman who used it” Plastic applicators that are flushed down toilets end up in the ocean which then causes many problems for many marine animals. Plastic decomposes at an even slower rate under water and most tampons are not decomposed in the ocean until they are consumed by marine animals. That in turn causes health issues for the animals, and sometimes suffocation and ultimately death. The number of tampon applicators found in the ocean is alarming “In 2009, The Ocean Conservancy’s International Coastal Cleanup project collected 20,000 tampon applicators out of 4 million total pieces of reclaimed plastic waste.” In addition to harming marine life plastic applicators also raise potential health issues for women. Some companies use phthalates to make plastic applicators, this specific chemical group “can be absorbed through the skin” The skin mentioned in this quote is not only referring to that of a human but also and animal who comes in contact with it. Because plastic applicators impact the environment so drastically it is highly recommended for women who do not want to stop using tampons to use tampons that do come with an applicator.

Packaging and Wrapper

The other components of tampons is the wrapper that each tampon is wrapped in and the box that they all come in. It wa very difficult to find information on the specific materials used in packaging. The box is made of cardboard which is then printed on with ink, as for the wrapper that emcompasses the entire tampon is most likely made of plastic fibers. As with the plastic applicator a significant amount of energy must be used to make them and a significant amount of waste must be produced although it is less than what is produced by the applicators. The environmental impact is present because it is a plastic, however this portion of the tampon produces the least waste and has the smallest impact on nature than any of the other parts of the tampon.

Consumer safety has been minimized in order for massive corporations to make profit. As mentioned before many manufacturers of feminine hygiene products are not required to report what methods they use to create their products. This has led women into oblivion in regards the materials in their tampons. While production today is monitored it is still important to note that these products still contain harmful chemicals. Regardless of how low the percentage may be it is not beneficiary for the consumer to increase their consumption of harmful chemicals and thus increase their chances of infertility, cancer or toxic shock syndrome.

Works Cited

"U.S. Food and Drug Administration." Tampons and Asbestos, Dioxin, & Toxic

Shock Syndrome. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 13 May 2015. Web. 01 Feb. 2016. <http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/PatientAlerts/ucm070003.htm>

Citrinbaum, Joanna. "TOXIC TAMPONS The Question's Absorbing: Are

Tampons Little White Lies?" Toxic Tampons. Collegian, n.d. Web. 01 Feb. 2016. <http://www.pureenergyrx.com/toxic-tampons.html>.

Chow, Lorraine. "Patent US4900299 - Biodegradable Tampon Application

Comprising Poly(3-hydroxybutyric Acid)." Google Books. N.p., 26 Oct. 2015.

Web. 03 Feb. 2016. <https://www.google.com/patents/US4900299>.

Directorate-General, Health & Consumer Protection. "Opinion on Genetically

Modified Cotton and Medical Devices." 28-29 JUNE 2001 (n.d.): n. pag.

Ec.europa.eu. EUROPEAN COMMISSION, 01 June 2006. Web. 01 Feb.

2016. <http://ec.europa.eu/food/fs/sc/ssc/out216_en.pdf>.

Dudley, Susan, Salwa Nassar, and Emily Hartman. "Tampon Safety - National

Center For Health Research." National Center For Health Research. HCHR, 27 Apr. 2010. Web. 01 Feb. 2016. <http://center4research.org/i-saw-it-on-the-internet/tampon-safety/>.

"How Plastic Is Made." PlasticsEurope. Association of Plastic Manufacturers, n.d. Web. 14 Mar. 2016. <http://www.plasticseurope.org/what-is-plastic/how-plastic-is-made.aspx>.

Kumeh, Titania. "What's Really In That Tampon?" Mother Jones. N.p., 20 Oct.

2010. Web. 01 Feb. 2016. <http://www.motherjones.com/blue-marble/2010/10/whats-really-tampon-and-pad>.

"Patent US4900299 - Biodegradable Tampon Application Comprising

Poly(3-hydroxybutyric Acid)." Google Books. N.p., 13 Feb. 1990. Web. 01

Feb. 2016. <https://www.google.com/patents/US4900299>.

Spinks, Rosie. "Disposable Tampons Aren't Sustainable, but Do Women Want to

Talk about It?"

The Gardian. N.p., 27 Apr. 2015. Web. 1 Feb. 2016. <http://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2015/apr/27/disposable-tampons-arent-sustainable-but-do-women-want-to-talk-about-it>.

Tamigniaux, Rachel. "The Environmental Impact of Everyday Things." The Chic Ecologist. N.p., 05 Apr. 2010. Web. 10 Mar. 2016. <http://www.thechicecologist.com/2010/04/the-environmental-impact-of-everyday-things/

"What Are Tampax Tampons Made of and Are They Safe?" What's in a Tampax

Tampon? Tampax, n.d. Web. 01 Feb. 2016. <http://tampax.com/en-us/tips-and-advice/period-health/whats-in-a-tampax-tampon>.

Maylin J. Murdock

Professor Christina Cogdell

Design 40A

14 March 2016

Life with Menstrual Cycles: Tampons & Embodied Energy

The history of Tampons go as far back to as fifteenth century BC, however the modern tampon used today has been available since it was patented in the 1930s. Subsequently, there has always been the drive in regards to the regulation of tampons, yet people don’t want to talk about the topic comes up. Even in a class setting, tampons become the elephant in the room and people are uncomfortable when they are brought up as a topic of discussion. Think tampons and some of the first things that come to mind are: women, cravings, body pains, Mother Nature, and “I’m not pregnant.” About 70% of women in the U.S use tampons, and on average a woman can use 16,800 tampons in her lifetime (Kohen, 1). Though we, as women, rely on them to be there, we don’t think about them and take them for granted. Yes, menstrual cycles can get the best of women, and sometimes all their energy, meaning that those tampons need to be there when needed. So where do we get those 16,800 tampons per woman, and what is the energy associated with it? Through a life cycle analysis, I’ve come to understand that the embodied energy of Tampons goes far beyond the woman’s body and surrounds the raw materials, production, and wastes of its basics. And by understanding this, I hope to raise a general awareness.

To achieve this goal, I have structured the paper into subsections that present the embodied energies of tampons from materials to waste. Again, the main takeaway points to understand are materials, production and wastes. As an aside, I recognize our population isn’t composed of two sexualities, but many, I use the title women and define it biologically as those who have female counterparts and experience menstrual cycles.

Raw Materials Acquisition

The main materials of the tampon itself are the bio-fibers cotton and rayon. Bio-fibers have distinct properties that allow the product to be useful. Cotton and rayon (viscose) are the main bio-fibers that make up the Tampon itself. Cotton is a natural fiber that requires a simple 7 step process that includes kinetic energy, both human and mechanical work, as well as chemical energy. Rayon is a cellulose known as viscose and it comes from trees. It has a more complex 19 step process that has 3 stages, harvest tress, pulp mill, and viscose rayon production (Barnhardt). It is similar to Cotton in that it includes kinetic and chemical energy. Even though these fibers have intensive energy needs, they provide wonders and have unique applications

…because of their low cost, low density, high toughness, reduced dermal and respiratory irritation, ease of separation, enhanced energy recovery and biodegradability. [And] natural fibers provide stiffness and strength to the composites, are easily recyclable… (Reddy, and Yang 26)

Cardboard for applicators and packaging are made from bio-fibers that are used for pulp and paper and come from rice and wheat straw and corn stover (Table 3). Similarly, cardboard formation requires the energies that also go into to harvesting and collecting cotton and rayon.

Manufacturing, Processing and Formulation

When it comes to manufacturing tampons, energy plays a big role. Three main points to consider would be the storage of fiber, (fiber) web formations and tampon assemblage (EDANA, Image). First, the fibers cotton and rayon go through a purification (bleaching) process which require mainly chemical energy. Then, the fibers are webbed using mechanical energy and further a form of secondary energy. After the fibers are webbed, they are used for tampon formation which as well conducted also by secondary energy source with human management.

Distribution and Transportation.

Distribution and transportation is a key factor in the life cycle of tampon. It is the transfer of raw materials to manufactures, manufactures to consumers, and consumers to waste. In all, it facilitates the Tampon’s lifecycle getting from point A to point B. For example, Tambrands located in Maine (where Tampax tampons are made) has to obtain the raw materials cotton, rayon etc. and in turn deliver it as a product to many distributors across the United States and overseas. This process in the life cycle makes use of fossil fuels turning the chemical energy of burning a liquid to a gas into kinetic energy, the movement of the transportation.

Use/Reuse/Maintenance and Recycle

Having considered materials and manufacturing, it’s reasonable to look at the overall use and maintenance of tampons. For the consumer, tampons are mainly a onetime use and shouldn’t be reused at all. It’s easy maintenance for the most part women use as needed and dispose of right after use, which only requires the renewable energy of human labor. Tampons aren’t normally recycled, however both the packaging and applicator can be recycled. Use and maintenance are processes that require human input and kinetic energy. For the industry, I can relate what I learned in regards to P&G Tambrands Tampons. As of 2011, Tambrands is landfill-free, the cardboard used is recycled, old tools for production go to an auction, and trash go to a waste-to-energy incinerator (Skelton 1). And now they continue to push for zero-waste and challenge the idea of sustainability in which they look to better routes in terms of energy efficiency.

Waste Management

In the final analysis, I discovered that the embodied energy and raw materials of a Tampon’s output have many pathways which effect the environment. That being said, waste is an important topic across all realms of products and appeals to our daily lives. For instance, garbage cans make most trash invisible, and toilets/ water systems take away our bodily waste. Now, imagine a life without garbage cans or toilets… Considering such ideas, I call you to focus on the Tampon as a disposable sanitary waste item (Ashley, Souter, Butler, Davies, Dunkerley, and Hendry 255). Tampons can take two main routes after use: being trashed or being flushed. On that note, I don’t have any stance on which is better and leave it to you to decide what’s best because for most (users) it’s to their own discretion. After being trashed or flushed, tampons become either solid waste, waterborne waste, or airborne waste, all of which have environmental effects (Figure 3). For clarity, I’ll separate ideas into ‘dry’ denoting trashed and ‘wet’ denoting toilet.

First, as a dry waste, the applicator and packaging that the tampons come in can be disposed of as recycling or trash as a solid waste that can lead to incineration (air emission) by thermal energy or landfill (land space). Similarly, tampons after use can take this same route.

Second, as a wet waste, the tampon after use can be flushed (waterborne wastes) down the drain and into the sewers that lead to blockages which require transport, materials and labor for repair and maintenance (kinetic energy). Or it can lead to sewer overflow that can take two directions as well. One being to the sea requiring repair and maintenance or the other that is to the pumping station. After the pumping station it goes to the water treatment plant (WTP) and can lead to blockage or waste material capture. Once the material is collected it can go to the incinerator or landfill. Incinerator can lead to environmental waste such as air emissions and solid waste. Landfill require land space and can also be an air emission.

In conclusion, the embodied energy of tampon truly exceeds the woman’s body in which the raw materials, production, and waste gather. From raw materials to manufactures, manufactures to consumers, and consumers to waste there is an intermediate step of transportation that requires fossil fuels and chemical energy. And at each time step in the process the embodied energies very from primary to secondary (electricity), thermal, chemical, and mechanical energy. Importantly, we as humans use our renewable energy both as a consumer and a producer. Overall, tampons would seem simple to make, but just like everything else it can be complex. With the idea that none of this is visible to us or made known to us, is what pushed me to take a stance on raising a general awareness particularly because this is an item consumers rely on. From this I find that not only should we be appreciative or proud of (our) menstrual cycles, we should recognize what’s in a tampon, and how much of it effects our environment as a whole. To think that tampons or menstrual cycles are uncomfortable to talk about, makes some people who experience them also uncomfortable, especially if it’s ‘their time of the month’. Which is a standard I hope to break down with this life cycle analysis because I bet most people couldn’t imagine a life without menstrual support products.

Bibliography

[1] Ashley, R. M., N. Souter, D. Butler, J. Davies, J. Dunkerley, and S. Hendry. "Assessment of the Sustainability of Alternatives for the Disposal of Domestic Sanitary Waste." Water Science Technology 39.5 (1999): 251-58. ScienceDirect. Elsevier Science. Web. 24 Feb. 2016.

"Cotton vs Rayon Production Steps - Barnhardt Purified Cotton." Barnhardt Purified Cotton. Barnhardt Natural Fibers. Web. 24 Feb. 2016.

Dodge, Matt. "Procter & Gamble to Expand Maine Tampax Factory." BDN Maine. Mainebiz, 13 Nov. 2012. Web. 12 Mar. 2016.

EDANA. TAMPONS FROM RAW MATERIALS TO YOUR SUPERMARKET SHELF. Digital image. Web. 2 Mar. 2016.

Gouda, H., et al. "Life cycle analysis and sewer solids." Water Science and Technology 47.4 (2003): 185.

Kane, Jessica. "Here's How Much A Woman's Period Will Cost Her Over A Lifetime." The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 18 May 2015. Web. 24 Feb. 2016.

Kohen, Jamie M. "The History of the Regulation of Menstrual Tampons." Digital Access to Scholarship at Harvard. Web. 24 Feb. 2016.

[2] Reddy, Narendra, and Yiqi Yang. "Biofibers from Agricultural Byproducts for Industrial Applications." Trends in Biotechnology 23.1 (2005): 22-27. ScienceDirect. Web. 24 Feb. 2016.

Skelton, Kathryn. "Reduce, Reuse, Recycle: Good Earth and the Electronics Dilemma." TechTrends TECHTRENDS TECH TRENDS 51.4 (2007): 3-5. 14 Jan. 2011. Web. 12 Mar. 2016.

Stacey E. Shehin, Michaelle B. Jones, Anne E. Hochwalt, Frank C. Sarbaugh, and Stephen Nunn, “Clinical Safety-in-Use Study of a New Tampon Design,” Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 89-99, 2003

"Tampon." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Web. 24 Feb. 2016.

US. Department Of Commerce, National Bureau Of Standards, Ruby K. Worner, and Ralph T. Mease. EFFECT OF PURIFICATION TREATMENTS ON COTTON AND RAYON 21 (1938). Nov. 1938. Web. 24 Feb. 2016.

"What's in a Tampax Tampon?" Tampax. Procter & Gamble, 2016. Web. 24 Feb. 2016.

Cassandra Enriquez-Morales

Professor Cogdell

DES 040

14 March 2016

Tampons: Waste

In monotonous routine and daily use, awareness of the environmental and social impact that waste of tampons has on our society is in oblivion; Therefore, I will be focussing on the solid waste, airborne, and waterborne impacts that tampons have in our society and how truly execrable their impact on our ecosystem is. Before I begin, I want to stress how important it is to understand that this presents demographics in the small scheme of things and does not include all that, along with tampons, truly is affecting our environment. In other words, this research is very limited to and based on information provided by other reliable sources conducted by foreign researchers so is not case specific to the U.S.. With this, I had great difficulties finding information solely about the waste line in America much less strictly about tampons. Also, my personal knowledge of organic chemistry and statistics is very limited and found it difficult to personally develop raw numbers of the true impact tampon-caused-waste has on the ecosystem besides the ones provided. Nonetheless, this research project was as much as a revelation to me as to any other ordinary civilian that is unaware of the impact that their ordinary use of domestic items have on our ecosystem and personal health.

Skipping the list of materials which tampons are made of, tampons are synthetically made and have amounts of plastic which means they’re not biodegradable. In other words, their speed of decomposition is extremely slow and can take up to 450 years to completely decompose. Unfortunately, tampons are being disposed incorrectly, most commonly by flushing them down the toilet, and besides the existential fact that the sewage system is being altered, our entire ecosystem is being put even more at risk.

Aesthetics is important in modern day life, but is that really a fair tradeoff for deminitiong personal health and environmental protection? Tampons in their nature simply give women more security and confidence in days of menstruation, thus, in a woman's lifetime, she will use an average of 12,000 tampons in which her menstruation will cover about 6-7 years of her entire life. And of those tampons, 23% are being flushed into the sewage system. During my research, the word ‘dioxin’ was being thrown around like it was nothing but in definition, dioxins are highly toxic chemical byproducts produced by bleached products which can be absorbed by organisms or released into the atmosphere whether it’s by natural decomposition or solid waste incineration. The FDA assures that there is only 1 parts per trillion of dioxin in a tampon, and in relevance to one tampon, this is quite a small number. But truthfully, the only way for this number not to sound alarming would be if only one tampon was used annually. In the U.S. alone 81% of adult women use tampons (roughly about 101979000 women) and if my math was done correctly, 1.12% of the entire tampon waste reported annually is dioxin. And if we add the U.K. into the equation, having .36% on their own, there is a total 1.45% of dioxin byproduct in tampon usage annually between those two countries. And historically, tampons became popular in the late 1920’s, around the time of the industrial revolution, with possibly higher dioxin byproduct release, so just imagining the total amount of dioxin in our ecosystem only produced by tampons from then to present is quite scary. And as if it wasn’t enough, dioxin exposure can lead to cancer, reproductive and developmental problems because of its extreme toxicity. It’s clear that dioxin does become an issue in the long run, so the FDA better be concerned.

Aside from the personal health concern, there is the rest of the marine and freshwater ecosystem to consider. Because of the sewage overflow, specifically studying tampons, there are habitat destruction and wildlife entanglement and indigestion occurring in waterlife. This occurs because animals may accidentally mistake tampons, among other products, with food and either choke or suffer indigestion and consequently die. Also, as discrete as society wants it to be, flushed tampons are dirty and completely unsanitary, this causes pathogens and malignous bacteria to build up in the ocean which can both affect marine life as well as human life. As infected as these waters become, so do the organisms that occupy them. So if tampons keep ending up in the ocean at the rate that it is now, with 340 million sanitary items flushed a year in Scotland along with the negative contribution that America and the U.K. make, contaminated water can pose the risk to humans, upon contact or consumption, of of contracting skin rashes, and even much more serious illnesses like hepatitis and cholera. Also, recreational opportunities near beaches would diminish as the water can potentially become toxic, acidic, or simply uninhabitable. Small scaled occurrences have already happened in U.S beaches where they have been closed for sanitary reasons where water is too toxic or simply contaminated by sanitary waste (8).

Similarly, with solid waste, landfill sites lack of oxygen; therefore, the decomposition of tampons becomes impossible. Unbelievably, for the natural decomposition of the cotton part of a tampon, which is around 6 months if they’re organic, they tend to degrade faster under certain temperature and in certain locations: Warm, dry and somewhat acidic sites.

It was when presenting the previous fact for the first time in discussion, it was one of our classmates who asked why was it that tampons along with other waste was being burned into the atmosphere if it’s hazardous. With this piece of information along with other facts was it that it was concluded that a decision has to be made whether airborne pollution or solid waste is should remain. With the slow decomposition of plastics, and synthetic fibers, solid waste incineration seems to be the solution as space needs to be made for incoming landfill that otherwise would end up in the ocean, rivers, or streets.

Tampons need to be talked about, not only because they’re just as real as the women that use them but because they’re one of the leading causes of marine pollution through sewage outflow ( which is just as real as existence itself!). Each menstruating woman disposes about 300lbs of menstrual products in their lifetime. With roughly about 101.9 million menstruating women in just America, reality cannot be ignored.

Works Cited

"Dioxins & Furans: The Most Toxic Chemicals Known to Science." Dioxins & Furans: The Most Toxic Chemicals Known to Science. N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Mar. 2016.

"Journal of Environmental Engineering - 131(2):206 - Full Text HTML (ASCE)." Journal of Environmental Engineering - 131(2):206 - Full Text HTML (ASCE). N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Mar. 2016.

Lunapads.com. Lun"Journal of Environmental Engineering - 131(2):206 - Full Text HTML (ASCE)." Journal of Environmental Engineering - 131(2):206 - Full Text HTML (ASCE). N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Mar. 2016.apads, n.d. Web.

"Marine Debris & Plastics: Environmental Concerns, Sources, Impacts and."Solutions. N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Mar. 2016.

"Scottish Government." Marine Litter Issues, Impacts and Actions. N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Mar. 2016.

Time It Takes for Garbage to Decompose in the Environment: (n.d.): n. pag. U.S. National Park Service; Mote Marine Lab, Sarasota, FL. Web.

"U.S. Food and Drug Administration." Tampons and Asbestos, Dioxin, & Toxic Shock Syndrome. N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Mar. 2016.

"Using Disposable Menstrual Products- What Are the Environmental Impacts?" Bleed With Pride. N.p., 26 Nov. 2012. Web. 14 Mar. 2016.

"What You Need to Know about Tampon Safety." National Center For Health Research. N.p., 27 Apr. 2010. Web. 14 Mar. 2016